All change, please!

This post has been updated and is now on a new version of this site.

This notice will remain online until 20 September 2016.

All change, please!

This post has been updated and is now on a new version of this site.

This notice will remain online until 20 September 2016.

Details, details, details!

Love this picture of Shenyang’s main station? (Brilliant skies, eh?)

Trouble is there’s no way to get into the station from this end. And this end of the station (which is its southern square) has a Metro Line 1 station. You need a 5-minute taxi ride to transfer from rail to metro here.

Neat Shenyang North station, right?

Big news: Its Metro station on Line 2 is at the opposite square (again, the southern square). This is the north entrance to Shenyang North. Riders are instead directed to the Qishan Road station, a couple hundred metres away.

It’s the total lack of attention to details that make riders feel like they’ve been toyed with. It begets them a bad attitude (especially those from the West). It’s like — Yes, there is a Metro station — right by the station, but you’ll have to walk miles to get there!).

I don’t take this excuse that “oh it’s still under works… (we might be missing the money)…” Cut the nonsense. How much does it take for you to finish up a station exit? Shouldn’t cost you the price of — like — an Apollo mission, right?

Let’s dump the laziness and get those rail-to-metro transfers realised!

All change, please!

This post has been updated and is now on a new version of this site.

This notice will remain online until 20 September 2016.

That’s zero metres above sea level, for the uninitiated. Some time ago, I joined my wife on a trip to the city of Qingdao (in eastern China). She had media business to do in Qingdao, so I went around the area while she got busy — I went as far out as west to Ji’nan (where I found my optimised English standards in use) and environs, as well as the cities of Zibo, Weifang and Gaomi.

Shandong finds itself at an HSR crossroads, although only some of its most important cities are linked to the national HSR system. There’s a 200-250 km/h HSR stretch from Ji’nan to Qingdao, which will soon have a newer 350 km/h addition. When that’s done, trains will take just over an hour to reach Qingdao from Ji’nan (at the moment, it’s upwards of three full hours).

The cities of Weifang and Zibo struck me as two cities I could really imagine myself living in. In Weifang I found wide, open spaces and (what else) a Starbucks and Pizza Hut, one next to the other, so I could do a little food refuge if a crass excess of seafood got me scared (I am, after all, a little more “continental” — remember Switzerland is a landlocked country!). Zibo, though, is a funny place. The city isn’t made up of just one locality, but a series — with the main city (Zhangdian district, Zibo) at the northernmost extreme. The main city district has a lot of buildings which remain those with a very 1980s / 1990s look; that’s no surprise given the fact that the city didn’t miss out on the first round of reforms (when Deng Xiaoping was around), but later rounds of reforms and development went elsewhere. My rail friend there told me that Zibo started off as a Tier 2 town, then was downgraded (unofficially) to something he calls “Tier 2½” — because it’s missing out on the latest round of reforms and opening up. A lot buildings in Zibo still retain the look they had two decades back; they money, in the meantime, has gone elsewhere.

Gaomi remained a sleepy town to me. Me and American-Chinese friend Will went there back in 2010; my granddad hails from there, so to give him a nice surprise, I picked up a train ticket from that town. I remember back in 2010 that when I went there, there was probably one major statue, a huge highway leading into town, and then all there really was — remained peace and quiet. They’re redoing the station — it’s showing its age, but is still incredibly busy.

I was also given a personal guide tour of Qingdao’s main station by station staff, who showed me how train crew got busy. Next time you board a train departing Qingdao early in the morning, just remember that you’re not the first onboard: the train pulls in an hour ahead and train crew have to prepare absolutely everything within around 30-40 minutes before they let passengers in. It’s work.

I hope to return to Qingdao soon — there’s a whole swath of eastern Shandong I have yet to totally explore!

The new Street Level China post features, which are published regularly on this blog by David, offer you a view of China from street level — uncensored, unrestricted, unmodified.

Face it, the future of the rails in China lies with HSR. High speed rail landed in China beginning in 2007 with the 6th Nationwide Railway Acceleration Campaign, when trains running as fast as 250 km/h were unleashed. In 2008, even faster speed demons were set loose, to the tune of 350 km/h. The conservative rail minister Sheng Guangzu, however, rolled back speeds in mid-2011, initially finding no plausible reason, but later “backed” by the Wenzhou disaster. A speedbump is not expected any time soon, but already, these machines, rolling at 300 km/h, have transformed the way Chinese people get from A to B.

Shijiazhuang’s new railway hub features 24 platforms (nearly five times the size of the original station), an elevated concourse many times the size of the old, Maoist-era-in-appearance building, and links to the upcoming Shijiazhuang Metro. Soon, cars may disappear altogether from the parking lot in the picture, as many people transfer from HSR to Metros. Already now, many people “park and ride” from this station to Beijing, Zhengzhou, or further afield; it will take most riders just over an hour on fast services to reach these metropolises.

China’s HSR network calls for 16,000 km of express rail, although speeds have been lowered in western China. These short-sighted moves are, however, proving themselves to be failed policies, the best evidence of which can be seen in eastern China. Here, a new 350 km/h line is planned in eastern China’s province of Shandong between the cities of Ji’nan and Qingdao. At present, trains run no faster than 200 km/h on the existing accelerated line. Just think of the benefits the new 350 km/h line can bring the ridership, as well as those along the railway line.

When all is said and done, and when speeds are improved once again, Beijing will only be 8 hours away from Hong Kong, 12 hours from Ürümqi, and 24 hours from the once prohibitively-remote city of Lhasa in Tibet. China’s new revolution is less about political doctrines and more about moving people elegantly from A to B in a highly efficient manner.

All change, please!

This post has been updated and is now on a new version of this site.

This notice will remain online until 20 September 2016.

Makers.

There — I did it this way because having two appearances of “makers” in the same sentence would sound kind of weird, no?

Lest you thought I aped Steve Ballmer, nope. It wasn’t an excess of some North American comedy either. Let me tell you guys one thing: the worst thing than can happen when your mouth is less than an inch away from the microphone — is to bore the living and dead #beep out of people. I’m not kidding you. I had those terrible lessons in my BEc years in university because that teacher sat in one of these positions:—

and delivered an (un)academic sermon for 90 minutes straight. Jeez. After 15 minutes, I gave it up and favoured a little Lonely Planet guide into Hong Kong.

Whenever I speak I favour a handheld mic for the simple reason it gets me away from the lectern. First, you’ve got to move your eyeballs, so there goes all that (potential) drowsiness. Second, you can actually do crazy things with the thing, as you’re no longer chained to any one place in particular. You also have total control over the crazy noises you do. These days in China, presentation counts.

And the content, too, by the way. Today in my two-hour lingo sermon (which thankfully had nobody sleeping; this is a major problem here in China), I proceeded to rip open Chinglish at face value and tell people what made this weird lingo concoction of ours up. Inspired were about 60 or 70 people in the increasingly internationalising (that’s a word, I guess!) community of Tuanjiehu in eastern central Beijing. Yep, senior citizens, but also young kids from universities in town. Turns out there were a few things of note:—

which was why we’ve Chinglish on our signs. I didn’t feel any better when I spotted a few more in western Beijing’s district of Mentougou (one of these folks I know who might be in charge of Chinglish is going to get a pretty stern warning from me soon), but rest assured — I’m here to get rid of the whole thing.

Don’t you feel much more at ease when you’re told to let passengers exit first instead of this random bit?… “After first under on, do riding with civility…”

Picture credit: Co-host Alison Zhou. I do radio programmes with her every Wednesday afternoon from 15:00-16:00 Beijing time. You can’t miss us; we’re also to be heard online at am774.com.

All change, please!

This post has been updated and is now on a new version of this site.

This notice will remain online until 20 September 2016.

I think I was still a kid when:—

OK. I digress — I went a little off on “Li’l Kim”. But still, even in the early 2000s (remember, this is the 21st century!), we used computers in ways that you had to save a file on one computer. And there was just about no way to finish it off on a second without emailing it to you! (Emailing yourself sure sounds weird, but oh well…!)

But then we had this weird thing called MediaWiki (and also WordPress) appearing. Suddenly, you could write stuff, save it as a draft (or as the real thing), and edit it on another machine without anything out of the blue happening. Then we had Dropbox. And now, cloud services, including Apple’s iCloud. Suddenly, we take the ability to start things on one device and to finish it off on another device — snap, just like that — as granted!

On the one hand, our lives have never been as digitised as today. You see it all in 7 year olds on high speed trains in our part of the world, who get busy with Temple Run whilst cruising at 300+ km/h. You see it in Yours Truly, who finished one tad of this article in Room A, and then gets the other part done on the Metro, before assembling it in another place — with probably another device.

We are living in an era of a completely different computing paradigm. Not only has Twitter fragmented information delivered to us, but we are also fragmenting our works. Are what we’re coming out with of a higher quality? Probably not — it’s hard to do a chef d’oeuvre when your mind isn’t exactly in one centralised place at one fixed time. But maybe it is the case, after all — if you suddenly hit upon the ideal blog post whilst commuting on Line 6, you can now finish it off in the office.

For better or for worse, we as computer-ised (let’s face it) humans have changed the ways in which we think, thanks to both the computer and, in particular, the Internet. We don’t even need to look at how different we’ll be by the 22nd century (God save me if I can still be here for this). We’ll look at ourselves in yet again a different computing-related paradigm by the end of this decade alone.

About 10 years ago, I’d have thought a trip to Changsha, South China, by train, would take maybe two or three days. Now, you do that in just about 5-6 hours on a fast train. About a decade back, I thought the Internet was only here to send emails and to do basic web pages where you tooted your horn. I never thought the era of the Internet became that where we are online by default (instead of being offline). Is the future scary? It’s not going to be the same as the past, that’s a given. It’s scary if you see black — and otherwise if you see any other colour.

Especially if you’re an optimist.

Ideally, a digitised one.

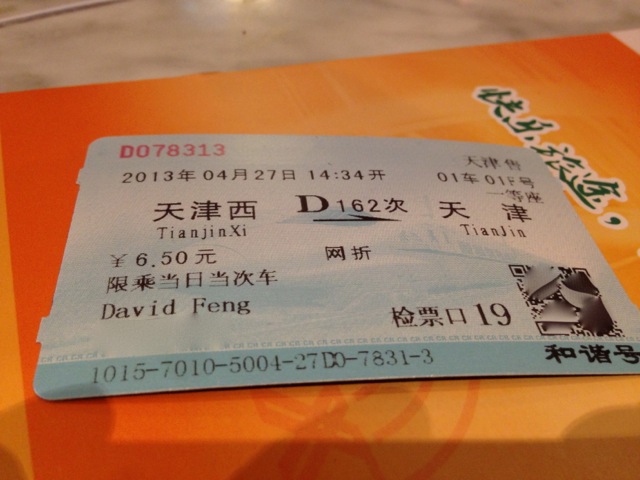

A train ticket I am proud of: the first David Feng ticket.

A train ticket I am proud of: the first David Feng ticket.

At present, my passport bears my name (especially my first name) that belongs to someone who used to use this name — before 2004. On the first day of that new year, I made it very clear that I will dump my Pinyin first name.

With good reason — previously, my Chinese Hanyu Pinyin first name (“Yan” Feng) spawned for a whole load of unauthorised would-be clones, such as…

…to the extents that the moment I approached a mic and read my name out, I felt great unease. I later told counselling experts that I was uncomfortable with using my Chinese Hanyu Pinyin first name in public — a major reason, obviously, being that the name would be toyed with. Nobody knew how to pronounce the thing. So obviously using a Pinyin name in the West was surely a tall order!

Obviously, I’m a “legal” kind of guy (simply put — the strict codes that were put in place by Switzerland upon its residents meant that there was a law for everything — men were supposed to sit on the toilet throne after 22:00! — and that was a pretty extreme example; and being resident in Switzerland, I became a strict follower of the law books). I was told that an instant registration re: the name change with the Swiss embassy was a bad idea — since nobody knew me with the new name (yet). So I decided to engage in a little bit of nomenclatural schizophrenia: I’d use my Pinyin name “with anything that has a .gov in it” (as in passports and diplomas, which have to be provided according to government ID names), but in everything else — such as media interviews, and more lately, train tickets in China, I’d use David Feng.

As of late, I’ve been using a crass excess of the name David Feng that now, if you Google me with my Pinyin first name (“Yan” Feng), you’d get this on the right hand side from Google (nicking its content from the Wikipedia):—

Yan Feng is a Chinese international footballer, currently playing for Dalian Aerbin in the Chinese Super League.

Oh excellent. And the first entry? “Yanfeng USA Automotive Trim Systems, Inc. held opening ceremony.” I’m a railways guy — I’d dump my car for the rails!

Meanwhile, if you help yourself to a Googling of David Feng, the first entry, bang-on, would be this website (davidfeng.com).

The increasing acceptance by all members of society at large of my new name, and my increasing prominence as David Feng, means that I’m now at a time and place where I have every last right — indeed, to prevent others from being confused, an absolute duty — to change my passport name to David Feng. It does society at large a massive disservice if they still have to get two names for me. And I’m not just on about the huge waste of ink…

My name is an absolute, inalienable human right. It does all of society a favour when my passport bears the exact same name as the name I use on an everyday basis — in particular if that name is one that I feel at home with. International conventions guarantee the right to a name as one of the most fundamental human rights. I will no longer go about daily business with a name which has been mutilated; I will be called the way I wish to be called.

I will be addressed by David Feng — and by no other name.

I’m hereby announcing something big:—

This means that on and after 01 May 2013, if you call me by my former name, I will only respond three times — every time with a notice about my name change. To make sure people are totally aware of the new name, I have to take such measures — but that will be for the good of society as a whole.